Credit

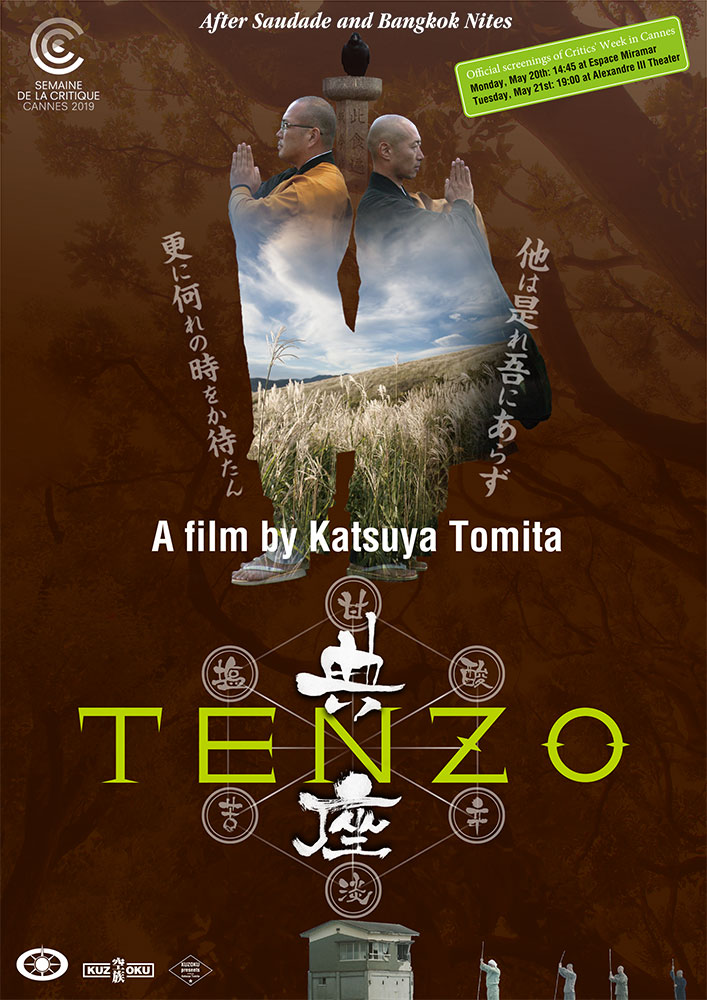

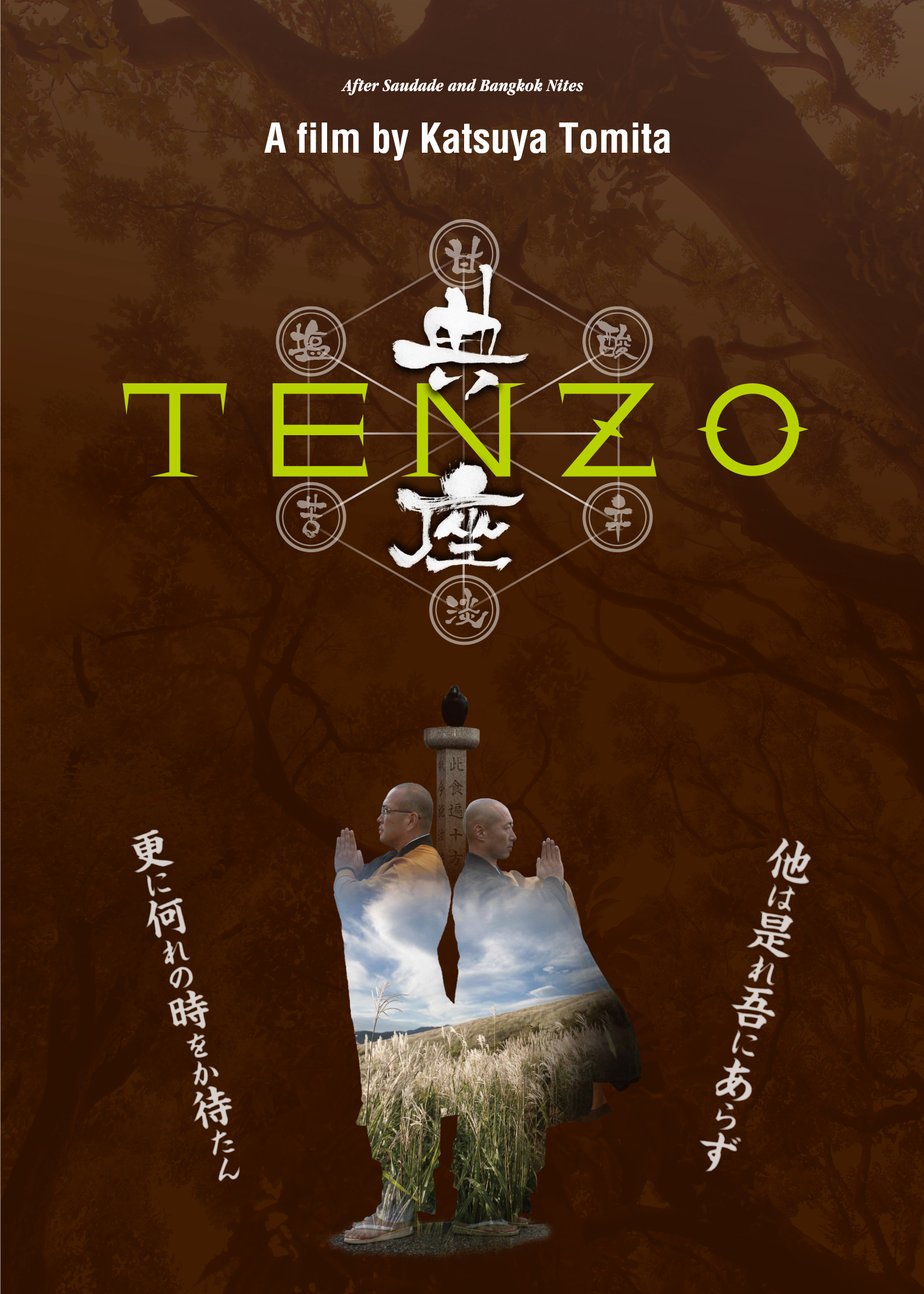

Japan / 2019 / 60 min / 1:1.85 / colour / 5.1ch / DCP

Presented by All-Japan Young Soto Zen Buddhist Priest Association

Producer: Ryugyo Kurashima

Director: Katsuya Tomita

Screenplay: Toranosuke Aizawa, Katsuya Tomita

Cinematography: Studio Ishi

Sound: Iwao Yamazaki

Music: Ubaguchi Takeno Kai, Suri Yamuhi And The Babylon Band, NORIKIYO

Title Logo: Yoshihiko Fujita (REBOOT.ARTWORK)

Visual Design: Hiroshi Imamura (LUGAR)

Still Photographer: Takahiro Yamaguchi

VFX: Masato Sadaoka

WEB: Shunsai Yamada

Painting: Masahiro Mukoyama

Cast: Chiken Kawaguchi, Shinko Kondo, Ryugyo Kurashima, Shuntou Aoyama

International Sales: Terutaro Osanai (Kuzoku Inc.), Atsuko Ohno (Flying Pillow Films)

All-Japan Soto Young Priests Association.jpg)

Directer / Katsuya TOMITA

Born in 1972 in Kofu, Japan. After graduating from high school, he saved money to make films by working as a construction worker and a truck driver. For three years, with an 8mm camera, he spent his weekends making his first film with his childhood friends as actors. Above the Clouds was released in 2003. With the grant he received with the film, he then shot Off Highway 20 (2007) on 16mm. In 2008, he started to make Saudade, based on the story of his hometown Kofu, which was partly funded by the people of the city. The shooting took a year and a half and the film was shown at Locarno International Film Festival in 2011. It won the Golden Montgolfiere Award at the Three Continents Film Festival in France. In Japan, 30,000 people watched the film in theatres, and it became a box office hit; it was also released in France the following year. In 2012, Tomita started travelling between Bangkok and Kofu, for the preparation of Bangkok Nites (2016). This fourth film, which deals with post-colonialism, was shot with locals across Thailand and Laos. It received its world premiere at Locarno Film Festival, and was released in Japan, France, and Thailand. Tomita’s films have travelled across the world at numerous international festivals, such as Jeonju (South Korea) and La Rochelle (France), seven of which have staged retrospectives of his work.

2003 ABOVE THE CLOUDS (8mm -> DVCAM, colour, 115 min)

2007 OFF HIGHWAY 20 (16mm -> DVCAM, colour, 77 min)

2009 FURUSATO 2009 (HDV, colour, 50 min, documentary)

2011 SAUDADE (HDV -> 35mm -> DCP, colour, 167 min)

2016 BANGKOK NITES (DCP, colour, 183 min)

Interview with Katsuya TOMITA

After depicting the social reality of your hometown in the face of globalization in Saudade, followed by the consequences of post-colonialism in Asia with Bangok Nites, your new project approaches Buddhism. How did Tenzo originate?

Katsuya Tomita: It’s rather rare in my case, but this film was commissioned by the Young Monks' Association of the Soto Buddhist school. Each year major festivals are organized across the world in a different host country gathering all the Buddhist schools. The last one was held in Japan. The Soto school who participated wanted to make a short promotional film presenting their activities. That was the initial idea. The funding came from the school. But since it's the second largest religious group in Japan in terms of importance and number of followers, when the Association launched their fundraising campaign they ended up collecting much more than expected. Thus from a very short film we ended up making a one-hour feature. However it's no coincidence either, since my debut feature shot in 8 mm, Above the Clouds (2003), had to do with a temple of the Soto Zen branch which happens to be my mother's family home. The main character was actually inspired by my cousin Chiken who plays himself in Tenzo. This film is therefore directly related to my family history.

Did you have any hesitations before accepting this commission?

KT: I agreed without thinking because I felt it was a sign of fate. I had already touched upon the subject in Bangkok Nites, but later on I realized it was latent since childhood. Chiken's father is my uncle and when I was a kid he would take me to visit Shuzenji Temple where he had gone for training. He showed me the wall you sit facing during zazen meditation for seven days. I even recited the Heart Sûtra, which I could easily memorize. I didn't understand too much about it but I was unconsciously permeated. I even said that my childhood dream was to become a monk. Making this picture was a natural calling.

Can you talk about the writing process? How did you go from a short film to a one-hour feature?

KT: The documentary interview between Chiken and Aoyama Shunto, the nun we see in the film, served as a mold. Their conversation was so enlightening that I wondered what this young monk's daily life was like and I created the structure of the film as a duality between Buddhism and the daily reality of the monks. That's when I started writing the script. After finishing the first draft I asked my partner and co-scriptwriter Toranosuke Aizawa to look into it. We rewrote it together and sent it to the Fukushima Monks' Association. They gave us their feedback and there were discussions because some didn't want us to show certain things, like monks drinking alcohol. Once the project was green-lighted we established a shooting schedule and went into production. The project evolved during filming and took over a year. The shoot kicked off at the beginning of winter and ended during the following.

What's the line between fact and fiction in relationship to writing?

KT: While talking with Chiken and the other monks, I began to draw from their daily life in order to depict their reality. Chiken's family stories, such as his son having food allergies, are all true. It's his real-life wife in the picture and his relatives play their own parts on the screen. So I drew fiction from their personal experience. Concerning the Fukushima worker-monk, he's played by Ryugyo Kurashima, the president of the Association and initiator of the project, but this monk actually existed. He was working on construction sites cleaning up debris left by the tsunami before committing suicide. His story inspired me to create this fictional character while showing an alternative to suicide was possible. Since Chiken asked me, I built the picture around his reality. Even though things are staged, everything that happens on screen could've taken place for real.

Chiken became a Tenzo, the head cook of the monastery. What is the status of this occupation?

KT: Even in Japan it's an unusual occupation because it only exists in the Zen Soto school. In the other Buddhist currents monks don't usually prepare their meals. I thought that would make a good gateway to introduce this school founded by the monk Dogen (1200-1253) who visited China over 700 years ago to complete his training. He was of aristocratic background. Japanese Buddhism was elitist at the time. When Dogen planned to sail to China he had to show great determination because it was a dangerous voyage. Nearing the coast he had to remain at anchor before he was able to berth. Each morning from his ship, he would see an old monk who came to buy konbu seaweed and dry it in the sun. They started to chat and Dogen was astonished to see such a venerable monk lower himself to doing such common chores instead of practicing zazen meditation at the temple to attain enlightenment. But the monk replied that: "Others are not there to do your deeds." Also they were in full sunlight and Dogen suggested that he could wait until the evening so that it was less hot, to which he replied: "Don't wait to do what you must do". That became the very first experience that destroyed Dogen's preconceptions on Buddhism. These are the two fundamental teachings he remembered which are summoned at the end and serve as the movie's catchphrase.

Chiken says he cured his allergies and asthma through his diet. What's the Tenzo regimen made of? Does it follow specific rules?

KT: As kids, our families would gather together during holidays and I remember Chiken would often be woken by asthma attacks at night and he was carried to the hospital. I witnessed it. He went to do his apprenticeship in the famous main temple called Eihei-ji, which Dogen had founded and which we seen in the picture's opening. It's a rigorous environment in which he stayed four years. At first, his body had trouble getting accustomed to this strict new regimen where you eat only twice a day: morning and noon. The morning meal consists of a bowl of rice porridge with small pickled vegetables thinly sliced and sprinkled with Japanese sesame salt. At noon, the meal is a little more substantial but they don't have dinner. There's a Japanese expression that talks about the "medicinal stone" cooking (yakuseki ryori). To quench their hunger the monks would lay on their bellies a stone heated by the day's sun. Additionally, the first Buddhist principle is avoiding food of animal origin, which makes it vegan.

You address the issue of food allergies through Hiro, Chiken's son who's hospitalized following an anaphylactic shock.

KT: Like many Japanese today, I had a rather folkloric image of Buddhism as a practice mainly used during funerals, but I discovered that these monks who had commissioned me to make this picture were very committed to their missions. When I asked them why, they all replied they had been extremely affected by the 3.11 disaster in Fukushima. One immediately connects the accident with radiation and its effect on environment. There can't be any worse environmental damage. More generally, the culture and production mode of vegetables in Japan is a major concern. The issue therefore became a key part of the film.

Why did you divide the film into flavours?

KT: In the basic doctrines of the monk's cuisine you only eat the minimum food necessary to sustain yourself. That's a fundamental ethic. The idea is that what the earth bestows must be reduced to strict necessity. It applies to all areas of life and implies a conception of the human being as part of world's metabolism. It's the same for taste which is made up of several flavours. Each flavour combined to another shapes a taste, like music. To each taste there's a matching instrument sound in the background. That's the reason for this structure. This vision inspired by Buddhist teaching applies to the form of the film itself.

Chiken also provides cooking classes to the community. Is it a way to pass on those teachings or to recruit new followers?

KT: Even the funeral-like Buddhism, which I mentioned, tends to disappear because it becomes more and more difficult to find space to preserve family graves. Recently in Japan new kinds of cemeteries have appeared that look like automated parking systems. It is the very existence of temples as heritage which is threatened. Monks became involved in such activities not because of doctrinal purposes but for the sake of economic management upon which the survival of temples depends. The benefit from the organic food trend is that it gives people the opportunity to delve into a broader interest for Buddhism.

It's also a way to restore connections within the community.

KT: Connection is a fundamental concept. If the monks stepped in through a superficial doorway and for economic necessity, they realised participants were looking for something else and were questioning the foundations of Buddhism. We felt a rise of interest as the current social context tends towards a growing insecurity of the individual. In many families each parent is forced to work, leaving their children in self-care. The communal solidarity doesn't function as well as it used to, and temples are places where people feel like relying onto again. Their role takes on a new meaning. That's the reason for increasing these types of activities.

Among those, you emphasize suicide prevention, to which Chiken contributes through a hotline. We learn that 30,000 Japanese commit suicide each year. You're depicting the state of Japanese society.

KT: Both among the monks and our film crew we had a deep feeling that times had changed. There was a period when Japan was very rich. We spoke about the bubble era. When people live in material wealth, who worries about faith? Religion didn't have a central place. In the last few decades, Japan entered a new era in which it's become relevant again. This observation underlies the whole film and transpires through the suicide issue. However the hotline set up by the monks has limited effects because the only thing they do is listen. They can't provide advice without taking responsibility, so their hierarchy prohibits them to do anything but listen. I used the hotline as a fictional device. There's a progression in the film where we see monks gaining more and more freedom of speech and cutting loose.

In our Christian roots a monk makes vows of chastity, but Chiken leads a lay life with wife and children. Things are very different in Japan.

KT: It's unique to Japan, even in Southeast Asia that's not the case. This comes from the hereditary system where religion is passed on through blood ties, which doesn't exist in other religions into which one enters by calling. Southeast Asia's Buddhism is a very ascetic form, which implies a total renunciation of one’s family and belongings. It's a rigorous practice closer to that of the Western monks. But during his establishment in Japan, a monk by the name of Shinran (1173-1262) rebelled against the idea that enlightenment would only be accessible to those who had renounced everything. His vision was more secular. According to him, it was possible to have family ties and own property while following an apprenticeship. It was at this time that a major schism happened. Later on, during a certain historical period, the political context led to this former branch and Japanese Buddhism was established upon the hereditary model. The nun claims that it was this system that corrupted Buddhism in Japan. It's a delicate issue in the film because at the same time she utters these harsh words, we see Chiken who's a monk’s son and a father himself.

Shunto Aoyama, the nun, says the political agenda of the "Danka system" was aimed at eradicating the rise of Christianity during the Edo period.

KT: It's difficult to sum up but on one side there was the hereditary system and on the other the "Danka system" that required every household to become affiliated to a Buddhist temple, thus creating a parish system. The temples therefore became responsible for the family registries. Each Japanese had to provide a temple certification hence proving his non-affiliation to the banned Christian religion. But the major political rupture took place during the Meiji era where a movement of rejection of Buddhism called "haibutsu kishaku" (literally "abolish Buddhism and destroy Shakyamuni") in favour of State Shinto was promoted by the government. Monks were consequently excluded from society and forced to return to a secular life. It was this decision combined with the hereditary system that contributed to the decay of Buddhism in Japan. It lost its position as state religion. When Buddhism ceased to be managed by the state, it told monks they were no longer needed and could return home back to a civil status. It was from there that temples gradually became a family business.

She also claims only nuns escaped this corruption.

KT: Japanese Buddhism remains predominantly male and nuns are set apart in Japan. The famous main dojo Eihei-ji which can be seen in the opening is forbidden to women. They had to establish their own places in parallel dedicated to women. In Japan there are only five temples run by nuns where a woman who wishes can go into training and become a nun beyond all contingencies. These temples follow neither the heredity rule nor the "Danka system".

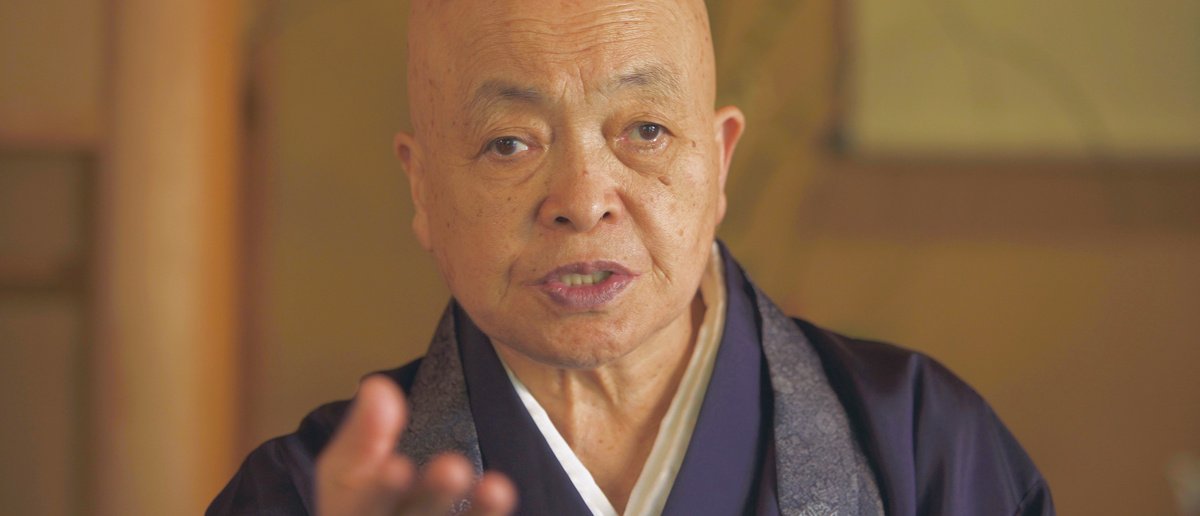

Shunto Aoyama is fascinating; she seems to have had an amazing life path. How did you meet her? Did you plan to film her?

KT: While preparing the movie I questioned the monks and asked them if there was any elderly figure that was advanced on the path of Buddhism who would be interesting to interview. They all pointed towards her. I wanted to shoot a crossed interview between her and Chiken and asked him to think about some questions he might want to ask her. During training to become a monk one practices "zen-mondo" which is an exercise of questions and answers between master and disciple. The disciple asks a question to the master and as the questioning progresses we approach enlightenment. It's through this dialectical impetus that the teaching of Buddhism takes place. Nowadays this exchange has become rather folkloric and has moved away from its original essence. So I tried to use this dialectical form in a metaphorical way in the film by staging this encounter between Chiken and the nun. The entire film crew along with the monks who accompanied us were mesmerized by her presence. To think such a woman exists in the world gave us hope. We tell ourselves all is not lost. She started learning Buddhism at the age of 5 and is now 86. She talked about her academic period. In Japan there's a Buddhist university where she enrolled. She ended up with sons of monks awaiting to take over the family temple. Most were there for mere opportunism. She was confronted with teachers who were mechanically teaching the words of Buddha and became frustrated because what interested her was to know how each one lived their faith on a personal level. We edited it out, but she complained a lot about the teaching which wasn't stimulating to her. Exhausted with that, she then took literature courses which interested her. But again she realized it was mere entertainment. So it's by giving up all her doubts and refusing a marriage proposal that she devoted her life to Buddhism. We shot about 2h30 of interview and I'd like to make a film just from these rushes.

Through the character of Ryugyo the monk-worker, you deal with the issue of Fukushima. How did shooting there come about?

KT: Like I said, the Fukushima disaster became major concern for all monks. 3.11 was a landmark in their self-questioning. We shared this feeling. We felt the event was triggering a return to religion. Depicting this reality was obvious. So we turned to the local monks’ association to collect their testimonies. We learned several of them had lost everything in the area. They saw their cemeteries devastated, their temples and families disappeared and they committed suicide in despair. So we decided to imagine Ryugyo's character, who would embody these desperate monks in the face of disaster. His position directly engages the foundations of Buddhism, such as the aforementioned "Danka system" and the hereditary issue. What is being a monk? Is being born in a temple enough to become one? Can one be a Buddhist after losing everything? We needed this character to question the essence of faith. His journey leads him to find faith by confronting himself to reality.

When a drunk Ryugyo falls into the back of his truck a refined dreamlike sequence shows him piercing the earth with a stick. What's the meaning of this image?

KT: This scene comes from the testimonies collected from Fukushima monks. They told me that when the tsunami wave retreated there was only a very thick layer of mud left. Monks along with firemen and Self-Defense Forces were requested to probe the ground with sticks, the same kind used for avalanches, in order to find enshrouded corpses in the ground. They stored the bodies in their trailers or in the back of their trucks and drove them to the crematorium. There was talk in the media because the crematoriums were so flooded they couldn't handle all the bodies. The monks stored them nearby while doing their prayers and went back. The presence of these monks and their prayers soothed the victims, as many of the bodies were not even identified. I wanted to use this scene as a dreamlike flashback recalling a life-changing experience.

A shot shows Ryugyo throwing up under a "Zen" sign. Was that meant as a provocation?

KT: Not at all. It was rather a nod to the previous sequence in which we see him with a bar hostess drinking from a bottle of "kokken" sake, the brand meaning "national power" in Japanese. He gets wasted from swallowing too much "national power" which drives him away from the path of Zen. When Dogen returned from his training in China, he was allowed to open his own temple with the recommendation to stay away from power and delve deep into the green mountains. That's the reason why he settled in Fukui to found the Eihei-ji monastery and the Soto school.

Ryugyo listening to rap while driving shows his militant side as well as monks having hobbies and personal lives. It's also evocative of your third feature Saudade (2011), in which rappers were at the forefront.

KT: In a similar vein, the fact that he's a construction worker also connects with Saudade, who dealt with workers from the Yamanashi region. For the record, a few years after Saudade's release, several workers lost their jobs as described in the film. One of them went job hunting in Fukushima. He heard they were hiring. One day I got a call from him saying: "It's paradise over here, I'm just moving rubble from one place to another, I could do it holding a beer. Come, it's a great deal!" This phone call indirectly links Tenzo to Saudade. So I'm planning to make Saudade 2 which will show the aftermath of 3.11. Tenzo is the bridge between the two.

One of the film's highlights is the voyage to China as a means to seek the original purity of Buddhism. Here again Tenzo connects with your previous feature Bangkok Nites and the initiatory trip of its protagonist Ozawa.

KT: Dogen the founder of the Soto school made this journey over 700 years ago. The idea was to replicate this twin experience and superimpose the image of the young Dogen with that of Chiken. It falls in line with my work on Bangkok Nites. We always try to adopt an outside point of view to take a different look at our experiences. The concept of travel is recurring in my work because it brings us into a different relationship to the world. Tenzo was a way of making a road movie with a monk while remaining consistent to my method of work.

The nun sums up the essence of Buddhism through the concept of interdependent origination. No phenomenon exists in isolation from others. Bringing together Ryugyo and Chiken at the end of the picture was also a way to visually materialize this concept.

KT: The nun says that if Buddhism is universal it should be applicable in all places. Each character seeks enlightenment under different circumstances. That's why I wanted them to meet in the end. Seeing them together embodied the idea that connections exist, even if their paths diverge. If I appeared on screen with our film crew, it's in the same line. Since it was Chiken who first offered me this project, everything's interconnected. At the end of the interview the nun says that even if it's only one man who attains enlightenment, it's meaningful. It wasn't only the monks who rose higher but myself as a filmmaker. I inserted this self-reflexive sequence at the end of the film to make that statement.

Enlightenment should be within anyone's reach.

KT: We edited it out, but during the interview with the nun she explained something fundamental to us: achieving enlightenment doesn't consist in discovering new knowledge. It's all about realizing, seeing and understanding why and how we got to where we are. It's a very concrete consciousness of reality. According to her, Buddhism and the search for enlightenment is not a way to escape pain or sadness. It mustn't be a flight but a positive quest. The last thirty years following the economic bubble have been difficult for Japan. I was lucky or unfortunate to live a careless youth during these years of overabundance. But after experiencing the Fukushima disaster I think it's really this bubble period that was abnormal. I realize more and more that Japan is destined to live a different reality. And I'm convinced that making this film at this timing is no coincidence. What comes into the background is that as money can no longer be an answer to happiness, it becomes necessary to turn towards the richness of the soul.

Interview by Dimitri Ianni

What is TENZO?

In a Zen temple, Tenzo is the name of the position given to the person responsible for the meals of all the residing priests and visitors to the temple.

In a monastery where monks live communally for spiritual training, the Tenzo is considered in the Soto Zen tradition to be one of the six most important administrative posts. The Tenzo is not only responsible for the kitchen and the meals, but also for teaching many important aspects of Buddhism.

What is SOTO ZEN BUDDHISM?

Soto Zen Buddhism is a denomination which regards, as its foundation, the teachings of the historical Shakyamuni Buddha, which have been properly transmitted from Zen master to Zen master over centuries.

Approximately 800 years ago during the Kamakura Era, Dogen Zenji brought the Buddha Dharma, which was transmitted to him, from China to Japan. Keizan Zenji then spread the teachings throughout the country. Together, they lay the groundwork for establishing the Soto school. Both are considered founders of Soto Zen Buddhism. Together with the historical Shakyamuni Buddha, they formed what is known as “Ichibutsu Ryoso” meaning “One Buddha and Two Founders”. The two head temples of Soto Zen are the Daihonzan Eiheiji Temple, located in Eiheiji Town (Fukui Prefecture) and the Daihonzan Sojiji Temple in Yokohama City (Kanagawa Prefecture). These temples are the source of all Soto Zen temples in Japan and the heart of our religious faith.

All-Japan Soto Young Priests Association.jpg)